I’m not sure I can write this. I damn well know I don’t want to. Thirty years gone from one of our last meaningful interactions and I still avoid the topic as much as possible. But staring at the list of important 1995 films and I cannot look away from the one title I really don’t want to rewatch.

If there is one adaptive technique I learned from my father’s alcoholism, it’s how to make myself quiet and disappear. Countless hours of my childhood were spent leaving the room as quickly and quietly as possible at the first sign of a raised voice or a shortened temper. The smell of beer was a sure sign to lock myself in my room, turn the television volume up enough to drown out elevated voices, and watch a movie standing a few feet in front of my old black and white set. Laying on the bed and making myself comfortable meant relaxing, which meant my guard would be down and the chances of being startled by an angry knock on the door increased. Being on the bed meant I couldn’t turn the volume down as quickly as would likely be drunkenly demanded, and although I never once had to do it, it meant I couldn’t make my way to the window and flee from a rampage if necessary.

I take that back. There were plenty of opportunities to hop out my first floor window and head for the safety and camouflage of the nearby woods, I just never chose to do so. When my father would bust into the room, easily shoving past the cheap lock, I would take whatever abuse he was prepared to dish out. Nine times out of ten it’d be limited to verbal abuse, itself limited by his slurred vocabulary. Each time I stood and took it, telling myself that “next time” I’d make a run for it, but I was admittedly a timid preteen, and my empty promises of bravery were hollow and stank of self-loathing and shame.

No matter how bad it got, I never ran away because there was a childlike optimism that the situation could improve. When sober, that’s exactly what my father would offer. Buried within his halfass apologies were declarations of sober days to come and a world where the constant threat of his hair trigger violence would end. Those days always corresponded with a refrigerator lacking his beverages of choice and would be emotionally recanted as sood as a six pack appeared. I wasn’t the only one in the family who couldn’t hold true to his word. By the time middle school was nearing its end I knew my father would never be able to quit drinking.

I’m sure a part of him knew this. He was renowned for his stubbornness, to force his ignorant will upon whatever dared stand against him, be it an engine that wouldn’t turn over, a tree that braced itself against his chainsaw a little too strongly, or my tearful mother begging for him to stop. As Captain Dudley Smith would say in L.A. Confidential, “It’s best to stay away from a man when his blood is up.” Well my father’s blood was always up, as was it’s alcohol content. If my father was in the house, it was best to just stay away.

He was seemingly a born alcoholic and was bound and determined to stay that way. He wasn’t going to change for no man, woman, or especially, child.

Writer John O’Brien understood this way of thinking, much to his own eventual demise. His book, Leaving Las Vegas, was a “brutal and unflinching” look at a man who shared my father’s determinism, only with a different set of end goals. When director Mike Figgis chose to adapt O’Brien’s tale of a man who slowly and spectacularly drinks himself to death, he knew he’d need to cast an actor who could portray that particular brand of self-loathing while still appearing sympathetic to not only the love of another battered soul in Sera, but also the audience. Those of us intimately familiar with alcohol abuse know that it’s not a breeding ground for heroes and the stories don’t particularly end well. While such a situation may give an actor numerous challenges, it presents an even tougher challenge for the audience. Can you like this human being who is dead set on ruining his life? Is that something that you won’t be able to look away from?

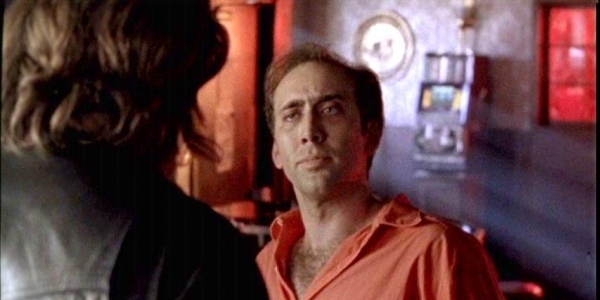

It’s a tough ask of any actor, yet alone one mainly known for his outlandish antics in Vampire’s Kiss or Raising Arizona. Despite my love of his portrayal of H.I. McDunnough, it was going to be nearly impossible for Nicholas Cage to win me over because even after half a decade of barely seeing my father, I wasn’t ready to see the worst of him projected up on the screen next to the girlfriend (and one of my first crushes) of The Karate Kid. I fully expected it to be sugar coated for the masses, or at least noble enough so that Cage wouldn’t come across as terrible as one particular real life alcoholic could be.

I shouldn’t have watched the film. I’d certainly seen some films that had challenged my worldview by this point, but I wasn’t ready for a movie to form a sharp stick and poke at all my well guarded hidden bits and challenge every lie I’d ever told myself regarding my trauma.

Throughout it’s nearly two hour run time I could feel myself becoming more tense as Cage’s character Ben begins his journey. We’re sold on the fact that while he is absolutely a drunk, at least it usually means he’s a happy drunk, trying to pass off as a charming lothario before the alcohol begins to take hold. He was a successful screenwriter. He had friends, many of whom still care about his well being. But he’s got a tragic backstory. As he puts it at one point, he’s not sure if his wife left him because he’s a drunk or he’s a drunk because his wife left him. Regardless of the impetus, the man before us is an absolute shell, pouring whatever he can down his throat to ease the pain.

Much like a briefly seen Valeria Golino, I was also not seduced by his charms. While he may be witty and verbose, I’d seen the far away, unable to focus, look in the eyes before at numerous family reunions that ended in fistfights or holiday activities that came to a crashing halt when threats became more commonplace than season’s greetings. Even in the safety of a darkened theater, my hyper-vigilism kicked in as soon as his voice raised an octave and by the time stuff started to break I knew where every emergency exit was. I was ready to flee, but much like I did during childhood I couldn’t bring myself to leave.

I watched helplessly as Sera, portrayed with endless empathy and wounded kindness by Elizabeth Shue in a career defining role, made apologies for Ben’s destructive and disruptive behavior, trying her best to laugh it off in hopes that bystanders would see it the same way and forget about it, not call the cops, not offer to help. I’d heard all the excuses that followed because my mother had made them all with two children in tow. As a child I wasn’t privy to what was ever said between them when it was just the two of them, when the anger had subsided and the danger had passed, but up there on the screen I recognized the look I’d seen in my mother’s eyes and it made me feel so fuckings small and angry because once again I was just a passive observer to all the bullshit and hurt and I couldn’t do one damn thing about it because that movie was going to continue to roll whether I wanted it to stop or not.

Of all the things that Cage, who rightfully one an Academy Award for his performance (and Shue, who was also nominated), got right in his portrayal, it was the acceptance of his situation and how hopelessness can hang off the face like an old Halloween mask. It’s a sad thing to witness.

When the movie ended I expected to be in tears. People die, people get hurt, lives get fucked up and horribly altered for the worst. I’d just spent two hours with my adolescent demons projected across one hundred feet of movie screen and was bludgeoned with it to the point of triggering PTSD. I should’ve been heartbroken.

Instead I was angry.

I was angry because Ben had succeeded where my father had failed. Ben had the tenacity, and more importantly, the financial ability to drink himself to death, even if it was in the company of a loved one. He had met his fucked up goal. My father, unlike Ben, liked to fight when he was drunk so there was always the possibility someone would’ve eventually kicked his ass while on a bender so badly that he would’ve had to detox while strapped to a hospital bed. There were few things my father was good at, but fighting while drunk was one of them so he only found himself at the police station from time to time, able to peacefully “sleep it off.” I cannot honestly say that I wish my father had met an untimely end while drinking, even during the worst of his alcohol fueled episodes, but there were times I certainly imagined how much easier my life would’ve been if just once he’d done something right.

But when I was barely twenty-one and seeing Leaving Las Vegas for the first time, I wasn’t fully aware of the effect that his drinking had on me. Some of the surface level acknowledgement was there. I barely drank through my formative years and on the rarest of occasions when I did, I didn’t drink to excess. And I absolutely abhorred violence. Even in the moments when I found myself in an unavoidable altercation, I didn’t fight back. I was always more scared of the thought that my father lived in me, just below the surface waiting for an excuse to come out, then I ever was of a punch to the mouth. A broken tooth was nothing compared to the thought of becoming him. So when Ben died, I was happy because Sera, for all her reasons for loving him, didn’t deserve to have him force his “twisted soul” on her any longer.

Perhaps if I, like Sera, had talked about what my father was like then perhaps I would’ve become aware of my trauma reactions much sooner. Maybe I could’ve been a better partner to those who chose to let me in, not always keeping myself guarded and distant when things became unpleasant or difficult. I’m certain I would have been better at communication and conflict resolution instead of my usual tactic of avoidance. It took me years to fully escape that, and by that point plenty of damage had been done. Years passed before I could move out of that shadow, able to feel safe when things went sideways.

Even now, the resolution still isn’t complete. Unlike Ben, my father isn’t dead, but for many years he was to me. I’ve seen him at the occasional holiday where my grandmother would consider it a pleasant surprise to invite my father without my foreknowledge. There have been random times where I’ve just encountered him out in the wild like stepping into poison ivy while hiking a trail. Most recently he was there at the passing of each of my grandparents, his parents. I couldn’t rightfully deny him a few moments of conversation, where I felt pity more than anything else, but I did at least speak to him, in a genial yet dismissive way. The moment needed to pass as quickly, and as peacefully, as possible.

There’s a million things I could say to him if I so wished. I could berate him for every terrible thing he ever did, describe in detail the horrors he put myself, my sister, and my mother through, before choosing to disappear so smoothly once my mother decided to kick him out of our lives. Every hurtful and hateful thought I’ve ever had would surely come spilling forth once the gate opens so instead I tell him things are fine when he sees me and let his calls go straight to voicemail when he attempts to follow up. He might be reaching out but I reserve the right to keep my hand pulled back.

Revisiting the movie was still difficult and I knew watching it after twenty years would still not produce a resolution for myself. As strong as I’ve gotten over the years, I’m not ready to fully revisit him yet, to pull those demons back out into the light for examination. These two thousand words have been enough for the time being. Ben might’ve had an angel in Sera, ready to forgive his self-destructiveness and hurtful behaviors and somehow still find the strength to love him despite everything.

I’m not ready to be an angel yet.